Prof. Temenuga Trifonova

LE STUDIUM Marie Skłodowska-Curie Research Fellowship

From

Department of Cinema and Media Arts, York University - CA

In residence at

InTRu (Interactions, Transferts, Ruptures artistiques et culturelles), University of Tours - FR

Host scientist

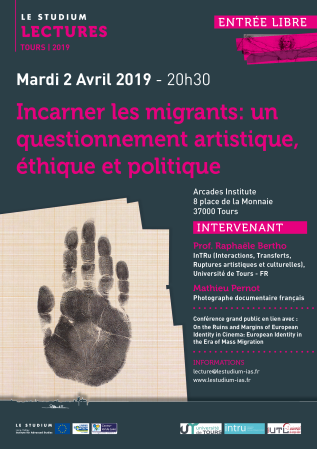

Prof. Raphaële Bertho

PROJECT

On the Ruins and Margins of European Identity in Cinema: European Identity in the Era of the Global

Recently, scholars have sought to re-politicize the discussion of globalization: we can point to Appadurai’s rethinking of the imagination as a political rather than a merely cultural fact, Ranciere’s insistence on the political potential of ‘the aesthetic regime of images’, or William Davies’s argument that neoliberalism, in extending an economic logic to all spheres of life, has come up against its own limits, making possible the ‘re-enchantment of politics.’ From this point of view, what Ranciere and Badiou have called ‘the ethical turn’ in the form of an “immeasurable debt to the Other’ may be seen as a manifestation of the destabilization of neoliberalism’s economic logic of rationalization. The ‘ethical turn’ has been accompanied by a simultaneous turn to self-loathing and self-flagellation; arguably, the most fascinating aspect of recent scholarship on European cinema and identity has been the transformation of the popular negative rhetoric of decline, decay, self-destruction, trauma, marginalization, Euro-skepticism, and Europhobia. For the editors of The Europeanness of European Cinema: Identity, Meaning and Globalization (2015) European cinema no longer defines itself in opposition to its traditional big ‘Other’—Hollywood; instead, “Europe itself may at times be the principal other in European cinema,” so that “negative perceptions of Europe – even Europhobia – [are] central to the Europeanness of European cinema” (11). Still, as they also remind us, too often Europe’s “self-deprecation is…a strategy signaling knowingness and a kind of perverse superiority” (11). This ‘strategic’ self-deprecation is evident in Elsaesser’s recent work, in which he argues that European cinema has been demoted to just another part of ‘world cinema’ only to rethink this ‘demotion’ as a golden opportunity for European cinema rather than a sign of its impending fade into oblivion since European cinema, now relegated to the margins, is free from the burden of having to reflect specific values or of having to represent the nation. I argue, however, that European cinema is by no means ‘free of having to reflect certain values’—on the contrary, it is expected to bear witness to a continually unfolding migrant and refugee crisis. My project explores contemporary debates around the concept of ‘European identity’ through an examination of contemporary European films spanning the period 2000 – 2018 to demonstrate that it is becoming increasingly difficult to separate stories about migration from stories exploring life under the conditions of neoliberalism.

Publications

Final reports

The increased mobility of large groups of people from outside and inside Europe has influenced the socio-geographical fixity of a continent of nation-states, putting in question both the concepts of ‘national identity’ and ‘European identity’. This book project considers contemporary debates around the idea of ‘Europe’ and ‘European identity’ through an examination of recent European films dealing with various aspects of globalization (the refugee crisis, labor migration, the resurgence of nationalism and ethnic violence, international tourism, neoliberalism, post-colonialism etc.) in order to reflect on the ambiguities and contradictory aspects of the figure of the migrant and the ways in which this figure challenges us to rethink core concepts such as European identity, European citizenship, justice, ethics, liberty, tolerance, and hospitality in the post-national context of ephemerality, volatility, and contingency that finds people desperately looking for firmer markers of identity. By drawing attention to the structural and affective affinities between the experience of migrants and non-migrants, Europeans and non-Europeans, the book argues that it is becoming increasingly difficult to separate stories about migration from stories about life under neoliberalism in general.